-

In many ways, the history of orange juice parallels the history of how a consumer culture has taken something healthy, over-produced and mass-marketed it, altered it completely and in the process stripped it of its natural goodness – and in the end, made it part of a wider health problem facing human society.

So how did that happen? How did something which grows on trees, something bursting with life and nutrition, wind up contributing to obesity? Well, the answer to the original OJ’s fate is arguably sadder than the fall from grace of a once-famous gridiron player turned homicidal bad actor.

In the beginning…

It all starts in the orange groves of Florida back in the late 1920s. Up until then, orange juice was more of a luxury, something experienced seasonally and freshly squeezed. See, the problem with oranges is they don’t ripen when they’re picked – in fact, the process of deterioration and loss of taste begins almost immediately. But as farming became more industrialised and orange production went through an unprecedented boom, the question for marketers was, “What do we do with all the fruit?”

Propelled by a celebrity-driven campaign spruiking its “health benefits”, canned orange juice began to be sold across all of America. It was pitched as a cure-all for general lethargy, sex drive and even an obscure ailment called “acidosis”. Sure enough, Americans bought in big time. Problem was, the juice lost its flavour (not to mention a significant proportion of its nutritional value) during the pasteurisation process. And not only that, demand wasn’t keeping up with the abundant supply. But there was a solution, and like many inventions, the military played a key part…

To concentrate, or not to concentrate?

At the advent of WWII, the US army was worried about scurvy-induced tooth loss among troops, but, weirdly, they had trouble convincing recruits to eat their sour-tasting lemon-crystal rations. Enter frozen concentrated orange juice (FCOJ)! After extraction, pasteurisation and ridding of pulp (which, ironically, we now know to be the most nutritional part), the juice was evaporated under vacuum and heat until the remaining liquid was about 65 per cent sugar. Essences, Vitamin C and oils extracted during the process were then added back later in combinations called “flavour packs” to restore taste and to give brands their own unique “taste sensation”. People were educated on how to mix FCOJ with water in order to “reconstitute” it, or it was repackaged as “ready-to-serve” orange juice (RTS). In either form, the product took off, dominating the market for over 30 years.

But as health became more of an issue in the early 1980s, a new product emerged as a winner. Not-from-concentrate OJ (NFC) certainly sounded healthier – if only people realised it meant flash-pasteurisation, de-oxygenation, de-oiling via centrifuge and then either freezing in 55-gallon drums or storing in stainless steel aseptic tanks for up to a year, after which time, now virtually tasteless, it would also be reinjected with brand-customised “flavour packs”. Mmm… just like sunshine in a glass!

Regardless, a glass of OJ became a staple of the Western breakfast. While the myth of “acidosis” had long been debunked, the idea of a vitamin C jolt to kick-start our day still resonated.

Back to basics

Eventually, though, people began to realise that real, non-pasteurised orange juice tasted better, and the market has been increasing steadily ever since. While Florida’s fabled groves struggle to compete with their Brazilian competitors for the OJ market nowadays, the question remains – is natural, freshly squeezed orange juice good for you? Well, yes… but mainly no. Admittedly, a standard 250ml serving holds 124 mg of vitamin C, contains potassium, thiamin and folate, the pulp is rich in healthy stuff called flavonoids and is also high in hesperidin, an antioxidant. But on the downside, one glass has 20.8 g of sugar and 112 calories… and that really is the rub. You see, we’re not actually meant to consume that much sugar in one gulp, and it’s a very different prospect to eating a whole fibre-heavy orange which gives our digestive process (in particular, our liver) time to process the sugars.

So, as a general health rule for life, rather than skolling orange juice – and certainly not FCOJ, NFC or RTS juice – you’re much better off eating a whole orange instead.

The history of orange juice

-

10 simple and healthy lunch ideas

Feast on our top 10 healthy lunch ideas.

-

The benefits of healthy home cooking

Explore the benefits of cooking at home.

-

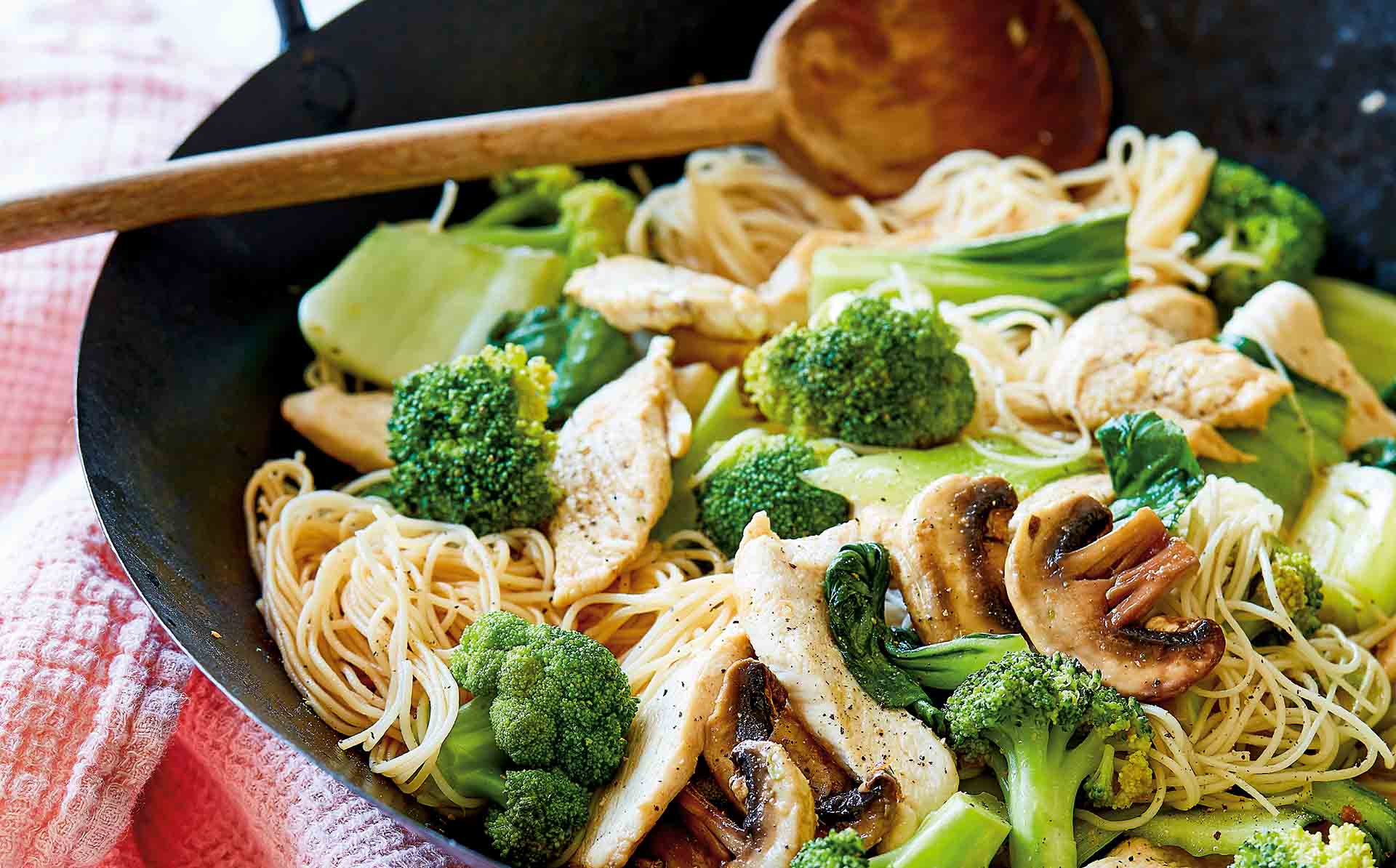

Chicken noodle stir fry recipe

An easy dish with the fresh tastes of ginger and bok choy.

-

Veggie-full beef bolognese with spaghetti recipe

Simple, delicious and packed with goodness, this pasta dish is an instant classic.

-

Is sharing a meal the secret ingredient to a happier life?

Why social connection may be the most important ingredient on your plate.

-

Chicken soup with parmesan, rice, peas and lemon recipe

Nourishing chicken soup

Subscribe to receive the best from Live Better every week. Healthy recipes, exercise tips and activities, offers and promotions – everything to help you eat, move and feel better.

By clicking sign up I understand and agree to Medibank's privacy policy